I picked up another half dozen books yesterday from the Oxfam in Chorlton; it was actually a specific trip there, as I'd not been for ages. I got W.N. Herbert's "Bad Shaman Blues", a Creation records "books sampler" (which I may already have...but probably not), a Richard Yates novel I'd not heard of before, another novel, and a fascinating looking book called "Recording Conceptual Art" with interviews with various artists that were made in the 1960s (the book is more recent.) There's a tottering pile of books on the table, that I've not yet looked at since another charity shop trawl on Monday, and there's a couple of things arrived in the post this week.

Looking at my packed shelves yesterday morning, I picked out Nicholson Baker's "The Size of Thoughts", a collection of his essays and started reading his essay from the mid-90s (published in the New Yorker, so available to subscribers), "Discards", which is an elegy for the library catalogue. Libraries are on my mind, as Manchester's magnificent Central Library reopens in a couple of weeks. There was some hoo-ha when it closed about books being got rid of or pulped; and I'm assured that the new library will still have books at heart its heart, though not necessarily as literally as before, where the book stacks themselves were the load bearing walls of the central dome. Yet there's a word of caution, when the word "books" is absent from that press release, yet "Apple Mac" computers get a mention. In fifty years we may well have no idea what an "Apple Mac" is (its a bit of anachronism even now - as their business has moved primarily to the iDevice motif) but we'll certainly know what a book is. Baker's article was a precursor to a later one about archives removing and destroying their "physical collections." This earlier article is a period piece, of course as we know how online catalogues and searches have changed since 1994. Nowhere does he predict that the internet might end up being the greatest "card catalogue" of them all; or that something like Wikipedia might enable the kind of army of fact checkers that he could never envisage. But he does quote the systems analyst Jim Bradley who talks of a "short dark age of scribalism as we transcribe from the original records into the electronic form" - a process that continues today (Google book search etc.) - but acknowledges there will be a "blot on the historical record." In other words - in the remorseless move of technology we'll gain much, (and he's been proven right), but in the transition something is lost, just as when we move from one home or city into another we may discard things in the clearout.

Some of Baker's caveats about electronic catalogueing are no longer an issue - or less of an issue - as searches are now far more intuitive than they used to be, though "colocation" (locating similar items together so that books about Madonna the pop singer are not inadvertently catalogued with books about the Madonna) remains problematic. We had a debate a few years ago about "search" vs. "social". I reckoned that "search" was the way that librarian's catalogued; not knowing the value of an item, but knowing the value of the collection; whilst "social" was the way people actually retrieve items, through recommendations or other leaps of logic. What I'd misunderstood, of course, was the extent to which librarians have always done this. That the catalogue is the early version of Amazon's recommendation engine. As Baker points out, a librarian might cross reference "Censorship" with "See also Freedom of Speech" whereas a computer might not knowingly understand the binary. In general we have moved on: but I've always said that there's a bit of a year zero for the internet - pretty much at the time of this article; and twenty years ago. Look up something prior to 1994 and its less likely to be on there. In other words, although Wikipedia, AllMusic, IMDB, the Internet Archive, and UbuWeb have done a fine job in many ways; they can never make up for the fact that only since 1994 has the digital record also been the contemporary record. Prior to that you need the physical artefacts, the newspapers, magazines and books of the day.

We are lucky that books are such steadfast items. They last well (though there's another erosion that surely takes place with the cheap British paperback of the last thirty or so years - already looking woeful compared to older versions); they are easy to store and index (their spine is a catalogue item in itself; their retrieval mechanism, the flickable page is unrivalled - replicated of course on electronic devices like the Kindle); and, most of all, pace Fahrenheit 451, we cherish them.

What Baker does say, which I think does sometimes get lost in the modernisation of our library estate is a simple thing. "The function of a great library is to sort and store obscure books." In other words: the role of the library is not purely that of the "lending library" with Catherine Cooksons and J.K. Rowlings read dozens of times; it is also about the unread. Manchester Central Library was, and is, a reference library, and acts as one node on a network of libraries throughout the UK. In other words, books don't necessarily need to be popular or read; but they do need to be stored, they do need to be catalogued and they do need to exist and be available. There have been some great initiatives in digitisation of late, that we shouldn't knock, such as the British Library making available PhDs online, 300,000 catalogued, 100,000 available as full digital texts, with others available on order. No one can surely deny the potential value of something like this, and the advantages it holds over pure paper based storage (And bear in mind that each of those PhDs will have a substantial reading list which will in itself be a mine of information). But of course, this is only possible because the paper was so carefully stored, and catalogued. Just to test it out, I looked up a friend's PhD from a few years ago, and it came up within seconds.

Yet we live in an age of unparalled publication - and whereas in the past, all books were ISBN'd, that's no longer the case. The "legal deposit" that I even did with our small magazine "Lamport Court" may well cover the majority of books, but not all. A friend - researching Manchester history - found the local newspaper archives brilliant until the eighties, but then as local newspapers became less papers of record (court reporting, government business etc.) our record becomes less certain. Hearing of a family friend who had passed away I went online to see if there was an obituary in the local paper, only to find that there isn't actually a local paper anymore. In this world the library becomes even more important as a professional resource. Its wonderful that Manchester and Birmingham, two cities built as much upon their intellectual property as on physical production, have recently invested so much in their city libraries, both of which I hope to see within the next month or so; but I wonder who would start a career in librarianship these days? Have qualified librarians been replaced by counter assistants? Not quite yet, but a librarian doesn't just value the contents of books, but the books themselves, though I accept that can be in electronic as well as physical form.

Like Baker's computer scientist, I'm an optimist regarding technology. Software, after all, is always in "beta", it gets better. (And then it gets worse, but that's another question.) But looking at a shoebox of old family photographs, you can't help but wonder where my shoebox will be when my time comes? There are whole periods of my life that aren't recorded - and no amount of Facebook timelines will replace that. There must be lots of digital "early adopters" who have fading self-produced photographs from around the turn of the century, and a non-compatible disc from a broken camera. I only hope you didn't keep your baby pics just on there...

We do learn things from the physical object - and maybe that's our job as much as the library's. Just as the BBC were incapable of storing their Dr. Who episodes carefully, or the legacy of iconic labels like Factory records or Immediate ended up in skips and lockups, after the company's failed, I'm no longer as sure that our library system is as capable of storing our contemporary media culture. There is too much, it is too fast, there is little compulsion on us to catalogue properly.

So I go round the secondhand shops, I create my own collection, haphazard, as yet uncatalogued - and I'm sure I'll use portable scanners, and online databases when the time comes - because not only does it seem the best way to have at hand much of the information I want, but its also vital in terms of context - whether I'm researching something for a poem or story, or simply wanting to understand more about a subject. We live in a rich country, a steady environment. One of the surprises I've had with Welsh and Scottish devolution is that more hasn't been done around cultural preservation. Imagine an independent Scotland - so much of its history and culture intertwined with England's yet spread out among museums and collections in both countries. Manchester has kept a commitment to its archives, libraries and other intellectual assets that is admirable, and - with the edifice of beautiful buildings as "cover" (for nobody gets nostalgic about a book warehouse on an industrial estate), if it hadn't been done now, I hate to think what a "privatised" public sector might have prioritised in five or ten years time. The irony about modern Conservatism is that the pull of its economic policies is anything but conservative. Yet all political parties are increasingly staffed and led by technocrats, who are the same administrators that Baker rails against. Like hospital bosses wishing they didn't have to deal with patients, a library administrator who's dismissive of the books and other assets that justifies his very existence is a liability waiting to happen.

My personal collection is tiny - personal and impersonal at the same time, but with a good eye to my particular tastes and directions of travel. I'm no completist, no first edition-ist, but I realise now, when I see a book that I've not seen before, there might be a sense that I never see it again. Self publishing, short run publishing, small press publishing - all these things are as ephemeral as yesterday's newspaper or your last Facebook status - but in them may lie greatness; but that hardly matters; any library - however small, however large - is more than the sum of its parts. For Baker's essay bemoaning the loss of the card library was saying something profound, but simple, that we don't know what it is we are losing. Anyone who has transferred their files to a new computer will be livid that the metadata on the original is so often lost, so that dates of creation are replaced with a new date, 1st January 2014 or whatever, the anonymous physical file has transformed itself, stripped itself of contextual meaning, because in the end it is only what we tell it to be, it is not an "it" in itself.

The Art of Fiction was a famous essay by Henry James, from 1885. This blog is written by Adrian Slatcher, who is a writer amongst other things, based in Manchester. His poetry collection "Playing Solitaire for Money" was published by Salt in 2010. I write about literature, music, politics and other stuff. You can find more about me and my writing at www.adrianslatcher.com

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Monday, February 17, 2014

My Writing

I'm not a doctrinaire kind of writer though I like the ideas of manifestos, and am more than happy to start a work from something "high concept" rather than the story or the characters. My writing covers fiction and poetry and I guess they have certain things in common: a tendency towards the contemporary, including referencing of pop culture; a political awareness - however slight, however non-party political; a general preference for the surreal, even if in a worldy context - i.e. at the edge of believability; an interest in language and form to tell a story; and, probably informing all of this, an unwillingness to manipulate the reader. I don't know if this makes me a particular type of writer - I do feel affinities with writers like David Rose, Lee Rourke, Nicola Barker, Magnus Mills, David Mitchell, Jon McGregor whose work inhabits imagined realities. I've referred to this kind of writing as "neurotic realism" in the past - in that it uses psychological and literary tropes over a, generally, realistic contemporary, to differing degrees. It interests me that there are a generation of writers who slip seamlessly between contemporary fiction and a sort of slipstream/fantasy work. It seems that the material might be mundane or everyday, but the approach is fantastical.

In this, I do think that I take bearings not from the American writers I admire, so much as that twilight British modernism: B.S. Johnson, Doris Lessing, Anthony Burgess, Michael Moorcock, J.G. Ballard and John Fowles that was primarily writing in the sixties and seventies. It is these writers, I think, that my generation - writers born in the sixties and early seventies primarily - take some kind of bearings from; rather than Murdoch, Lodge, Golding, Kingsley Amis, John Wain, Graham Greene, etc. Heirs of Huxley more than Orwell perhaps. Those influences I perhaps had growing up - Martin Amis and Ian McEwan - I've mostly shaken off; I think due in part at least to be the different times in which we've lived. Their best books have a cold war sensibility, in Amis's case a mordantly funny existentialism living under fear of the bomb; in McEwan's a sense of never-ending middle-class dread that shows his debt to Golding at least. We've lived in more straitened times, and I think our writing is less concerned with the winds of change, than in how we can carve out our own oasis. Remove the memories of the Second World War, and the existential threats of nuclear bomb and Russia, and our fiction plays out in a more demarcated space.

I'm not sure whether or not that equally informs my poetry, but perhaps it does. I'm rarely confressional; though might write about real things, and do think the tendency to the autobiographical is part of that "reality hunger" that David Shields refers to. Without an audience, its hard to know what kind of "audience" one is looking for, but coming from a pretty average background, I've always been democratic in my aims, even if I'm sometimes auto-didactic in my methods. I want to write a work that dumbs up, not dumbs down. Poetry, of course, obsesses about style and schools, and the idea of shifting on an axis that coincides with both formal and experimental schools at different times seems to be at odds with this binary. I think one is constrained here by the poetry I grew up with, even into my twenties, where Eliot and Pound aside, modernism was hardly mentioned, let alone anything since. Its perhaps not surprising that I have at various stages found much to admire in Lowell, MacNeice, Browning and Gunn, poets who have made leaps or slithers across the same glass; or simply through their own originality, can be co-opted by one side for their strangeness, and rejected from the other side for the same. Lyric poetry, like the short story, is a writing that denies itself a place in manifestos - partly because it is too small to align, but also because they are both malleable enough forms to do both things. My longer fiction never made it into publication, but has an equally uneasy relationship between the everyday and the surreal.

So as one continues to write, its surprising how little one has boxed oneself into a scene or an attitude. I'm somewhat pleased, if a bit perplexed by this. Perhaps I'm always going to be a project writer finding interesting things to do or say in different places, and finding the right apparatus to do so. This approach sees me more as one of those divergent artists who experiments with a range of styles. Yet I'm far from being a polymath, these adventures feel minimalist, un-showy. I'm not sure there is much of history of minimalism in literature outside the haiku and the poetry of Ian Hamilton, yet it surely has always existed. It perhaps has to mean different things in narrative writing than in the showing of fire bricks of four minutes or so of silence; yet I think it can be there.

Looking at the work I've done over the last couple of years it seems perplexingly diverse, unconnected to itself, yet over my whole writing life I return to themes, I stay somewhat within the parameters of my somewhat limited experience, and yet I automatically jump into different spaces when the work requires it. Every story and poem is different, and the idea of being able to write a book of poems or stories that are connected either in style or subject, would seem an impossibility, yet I would baulk at being called a dilettante; for the underlying themes of my work are often quite consistent; there's a constant moral and aesthetic centre, which only makes sense to describe in relation to the work itself, which of course, I would hope does the describing for me.

In this, I do think that I take bearings not from the American writers I admire, so much as that twilight British modernism: B.S. Johnson, Doris Lessing, Anthony Burgess, Michael Moorcock, J.G. Ballard and John Fowles that was primarily writing in the sixties and seventies. It is these writers, I think, that my generation - writers born in the sixties and early seventies primarily - take some kind of bearings from; rather than Murdoch, Lodge, Golding, Kingsley Amis, John Wain, Graham Greene, etc. Heirs of Huxley more than Orwell perhaps. Those influences I perhaps had growing up - Martin Amis and Ian McEwan - I've mostly shaken off; I think due in part at least to be the different times in which we've lived. Their best books have a cold war sensibility, in Amis's case a mordantly funny existentialism living under fear of the bomb; in McEwan's a sense of never-ending middle-class dread that shows his debt to Golding at least. We've lived in more straitened times, and I think our writing is less concerned with the winds of change, than in how we can carve out our own oasis. Remove the memories of the Second World War, and the existential threats of nuclear bomb and Russia, and our fiction plays out in a more demarcated space.

I'm not sure whether or not that equally informs my poetry, but perhaps it does. I'm rarely confressional; though might write about real things, and do think the tendency to the autobiographical is part of that "reality hunger" that David Shields refers to. Without an audience, its hard to know what kind of "audience" one is looking for, but coming from a pretty average background, I've always been democratic in my aims, even if I'm sometimes auto-didactic in my methods. I want to write a work that dumbs up, not dumbs down. Poetry, of course, obsesses about style and schools, and the idea of shifting on an axis that coincides with both formal and experimental schools at different times seems to be at odds with this binary. I think one is constrained here by the poetry I grew up with, even into my twenties, where Eliot and Pound aside, modernism was hardly mentioned, let alone anything since. Its perhaps not surprising that I have at various stages found much to admire in Lowell, MacNeice, Browning and Gunn, poets who have made leaps or slithers across the same glass; or simply through their own originality, can be co-opted by one side for their strangeness, and rejected from the other side for the same. Lyric poetry, like the short story, is a writing that denies itself a place in manifestos - partly because it is too small to align, but also because they are both malleable enough forms to do both things. My longer fiction never made it into publication, but has an equally uneasy relationship between the everyday and the surreal.

So as one continues to write, its surprising how little one has boxed oneself into a scene or an attitude. I'm somewhat pleased, if a bit perplexed by this. Perhaps I'm always going to be a project writer finding interesting things to do or say in different places, and finding the right apparatus to do so. This approach sees me more as one of those divergent artists who experiments with a range of styles. Yet I'm far from being a polymath, these adventures feel minimalist, un-showy. I'm not sure there is much of history of minimalism in literature outside the haiku and the poetry of Ian Hamilton, yet it surely has always existed. It perhaps has to mean different things in narrative writing than in the showing of fire bricks of four minutes or so of silence; yet I think it can be there.

Looking at the work I've done over the last couple of years it seems perplexingly diverse, unconnected to itself, yet over my whole writing life I return to themes, I stay somewhat within the parameters of my somewhat limited experience, and yet I automatically jump into different spaces when the work requires it. Every story and poem is different, and the idea of being able to write a book of poems or stories that are connected either in style or subject, would seem an impossibility, yet I would baulk at being called a dilettante; for the underlying themes of my work are often quite consistent; there's a constant moral and aesthetic centre, which only makes sense to describe in relation to the work itself, which of course, I would hope does the describing for me.

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Minimalism Maximilism

The art year is kicking in strong. There were two galleries with openings in Manchester last week. On Thursday I went for a "catch it while you can" "launchpad" show at Castlefield Gallery. Jenny Core's curated show, "The Drawing Project" is only one until next Sunday, but go see it whilst you have the chance. All artists "draw", often as the work in progress, sketching out ideas, or filling notebooks. This show brings out the hidden nature of this transitory work in a number of intrigueing, often minimalist interventions that see the Gallery opened out again after a number of shows where bits have been cordoned off. Its a quiet, subtle show, but not without its surprises. Clare Weetman's video installation of a residency in Istanbul, and Hondartza Fraga's minimalistic multimedia works in particular are highlights.

Contemporary galleries like Castlefield are able to showcase subtle works well, but when we look at our great public galleries, such as Manchester Art Gallery, we expect something of "scale". More recently, Manchester Art Gallery has shown willing to open out all aspects of the building, and no more so than in the new exhibition by Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos. Her "Time Machine" exhibition gives this versatile artist the opportunity to explore a number of different forms - but what they all have in common is a sense of scale. Vasconcelo's work is a like that of a surreal feminist Terry Gilliam; from the giant textile baubles hanging in the atrium to the remarkable room filling installations of the main show, to her interventions in the existing collection, there's a confidence about these pieces that not only need to be seen to be understood but to be lingered in. In the main exhibition, there are only a few major works, but each of them will repay audiences from lingering longer than you might usually do. Seeing the gallery taken over by such unusual chimeras made the preview audience gasp with surprise, but also laugh at her humour and audaciousness. The MAG show is on for a while - and, though I didn't have time to check it out at the preview - is alongside an appropriate re-hang of twentieth century sculpture from the gallery collection.

Contemporary galleries like Castlefield are able to showcase subtle works well, but when we look at our great public galleries, such as Manchester Art Gallery, we expect something of "scale". More recently, Manchester Art Gallery has shown willing to open out all aspects of the building, and no more so than in the new exhibition by Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos. Her "Time Machine" exhibition gives this versatile artist the opportunity to explore a number of different forms - but what they all have in common is a sense of scale. Vasconcelo's work is a like that of a surreal feminist Terry Gilliam; from the giant textile baubles hanging in the atrium to the remarkable room filling installations of the main show, to her interventions in the existing collection, there's a confidence about these pieces that not only need to be seen to be understood but to be lingered in. In the main exhibition, there are only a few major works, but each of them will repay audiences from lingering longer than you might usually do. Seeing the gallery taken over by such unusual chimeras made the preview audience gasp with surprise, but also laugh at her humour and audaciousness. The MAG show is on for a while - and, though I didn't have time to check it out at the preview - is alongside an appropriate re-hang of twentieth century sculpture from the gallery collection.

Saturday, February 15, 2014

The Seven Ages of Prince

1. R&B Auteur

He begins, like so many others, a 70s soul and funk artist, and his self-performed/produced debut was standard fare for the times. It was false start, only the lewd "Soft and Wet" hinting at what was to come, as he seemed to make clear on the sophomore collection by calling that one "Prince." Here he is half naked, staring at the camera, a skinny guy with long hair. The record includes his first hit, "I Wanna Be Your Lover," a brilliant piece of new wave dance pop; "I Feel for You", a later number for Chaka Khan, "Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad?" and other deep cuts that are well worth replaying.

What came next was a sidestep but an important one. "Dirty Mind" is one of the great funk records of the era, and his "blackest" record outside of the disputable "Black Album." "When U Were Mine" is the pop hit, but its the sleazy title track and the raw minimalistic "Head" that gave this album its rep. Not such a big record at the time - and virtually invisible in the UK at that time - its the album that really showed that he wasn't keen on just being the "next" Rick James or similar. 1981's "Conspiracy" continues in the same vein, but on the cover he's a suave southern gentleman, edging towards his purple period.

2. Global Superstar

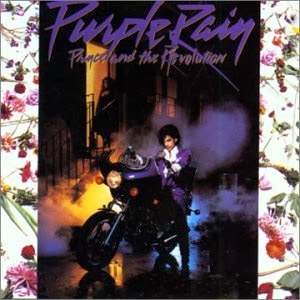

Prince's 5th album "1999" was a crossover record. A mostly successful double album (he still plays deep cuts like "Something in the Water" and "Let's Pretend We're Married" in his live set) its nonetheless not any kind of prog rock statement but a series of killer dance grooves. The epoch defining "1999" and rock crossover "Little Red Corvette" amongst its massive hits. He was toe to toe with Michael Jackson at this point, "Little Red Corvette" his "Beat it", before "Thriller" hit the stratosphere. You wait twenty years for a black superstar and then two come along at once.... the control freakery had been lessened somewhat as "1999" features a named band, The Revolution. "1999" - the single - made him visible in the UK, but there was still a sense that he was a niche artist, R&B, dance floor music. The next record saw an end to that. "Purple Rain" might be the most achieved statement in rock history since "Sgt. Pepper." A mega selling record, that was actually a soundtrack to a low budget but elegantly classic film of the same name. Prince, the recluse, plays "the kid" in this "A Star is Born" style movie. But the songs in the film are perfectly placed telling the story; and even better, are utter classics. "When Doves Cry" came as the preview track, and what a preview it was - terse, minimalistic tale of domestic violence - eschewing a bass line for a staccato beat - it was a massive hit. "Lets Go Crazy" was a successful retread of "1999" whilst the epic "Purple Rain" was a guitar anthem to match Guns N' Roses or Lynyrd Skynrd. With this record and movie Prince had turned into a megastar.

3. The Imperial Phase

Six records in, Prince had made it in every way. His songs were being covered by other artists - he was acting as a mentor to chart acts as diverse at the Bangles and Sheena Easton, as well as fuelling spin off acts like the Family, Madhouse, The Time, Sheila E and others. A "Purple Rain Pt. 2" would have been expected but instead he used this platform to go left field. "Around the World in a Day" was a surprisingly tentative record. Its first single "Paisley Park" more notable for naming his new studio; whilst "Raspberry Beret" was a Beatlesque piece of power pop. Long tracks like "The Ladder" and "Condition of the heart" spoke of a more ambitious musical canvas. Yet it was a sidestep from "Purple Rain" and sold much, much less. There was no film this time - though the crassly psychedelic cover hinted at the film in the listeners head. Tellingly it wasn't really a soul album at all. Having moved our expectations, the next record "Parade" was remarkable. A film soundtrack to the black and white "Under the Cherry Moon" this fantastic record is an art pop masterpiece yet includes bonafide number one hits (in the US at least) in "Girls and Boys" and the skeletal "Kiss." Where did this come from? There are jazz interludes, and the beautiful Joni Mitchell-esque "Sometimes it Snows in April." A near perfect record that most artists would never have been able to top - the news that his next record was a double (like "1999") got us excited, but not as excited as the first single. Prince "first singles" had become a tradition - sparse, maverick and ahead of the game, "Sign O the Times" was a beautiful bleak song about crack addiction. The double album was mostly without the Revolution. Prince in his studio churning out hardly finished demos. Not since "Revolver" had a major record been so scrappily produced. Yet he knew what he was doing. In the over produced eighties, simple sounding tracks like "Hot Thing" sounded underproduced but have remained fresh years on. Its a treasure trove. The frankly amazing "If I was Your Girlfriend" (Prince as lesbian), the rock pop "U Got the Look" (Prince as Roxette), the new wave "I could never take the place of your man" (Prince as the Cars), the beautiful ballad "Adore"(Prince as Smokey) and the live funk jam "Its Going to be a Beautiful Night" (The Revolution as Parliament) among its treasures. Despite an opening salvo in "Alphabet Street" as good as any of his other first singles, the next album "Lovesexy" was transitional. It ran as a single sequence - its intricately produced, a studio record first and foremost. It feels like his first record made specifically for CD. It came out after rumours of a dark funk record "The Black Album" leaked - and only one track from the latter made the cut here.

4. Prolific Pop Prince

Prince fans were the luckiest fans in the late 80s. Whereas Michael Jackson took years between records Prince was ridiculously prolific, and each of his last four or five records had been an advance, musically, if not in sales, on the former. It couldn't go on. Not that the albums after "Lovesexy" were bad, but they no longer had the shock of the new. Sometimes there was a sense that he was spreading himself too thin - e.g. on the soundtrack to "Batman", very little of which made the actual film, or on the sprawling "Graffitti Bridge" where acts on his record label such as Mavis Staples made guest appearances. The new wave and sinewy Revolution had been replaced with a new band, the more funky, live-focussed New Power Generation. If "Batman" was a soundtrack that wasn't heard in the film, "Graffitti Bridge" was a soundtrack to a film (his third) that nobody really watched. The songs are occasionally filler though "Thieves in the Temple" was a big hit. Perhaps realising he was losing his audience a bit, his next album, "Diamonds and Pearls" was his biggest pop record since "Purple Rain" and songs like the title track, "Get Offf" and "Cream" were bonafide classics to add to the collection, the latter another to his collection of U.S. number ones. Next time we saw Prince he was in dispute with his record label, the word "slave" on his face, and a new "symbol" replacing his own name. Ridiculously perhaps, he became known as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince as he extricated himself from his Warner Bros. contract. The "symbol" album was hardly affected - it included the self mythologising rap "My Name is Prince" and unplayable on the radio "Sexy MF" - his most jazz influenced song since "Controversy." With 3 double albums in a row, and rumours of much unreleased material, the next record, the underwhelming funk album "Come" was perhaps a letdown. Yet these years though hardly imperial still saw Prince in the 90s as a major star, with many pop hits. The albums that followed would be enough for most artists' career - the poppy "The Gold Experience", the finally released "The Black Album", and the somewhat scrappy "Chaos and Disorder" were topped with a triple CD, "Emancipation". All contain gems. During his dispute with Warners, a self released single "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" became his only UK number one (though he has written number ones for Sinead O'Connor and Chaka Khan.)

5. Emancipated Prince

Part of the Warners dispute had been Prince wanting to release what music he wanted when he wanted rather than following some kind of career path. Yet we'd seen how prolific his discography was. Emancipated Prince would release and market his own music. The long rumoured quadruple album "Crystal Ball" came out on his own label, and was an archive trawling exercise, matched by Warners on the forgetable "The Vault". Prince albums for the next few years would be far from being "events" slipping out unnoticed, marketed directly to fans or by mail order (or in the early 2000s as internet downloads). "Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic" was licensed to a new label, but sold poorly. Prince continued to play live - but often his sets had nothing in common with his latest record, and versions of old songs were stretched out, funkified, changed beyond recognition.

6. Back in the Game

The diminishing returns of this fan-club only Prince were suddenly reversed in 2004 with a reinvigorated Prince putting "Musicology" out through a major label. This and the following "3121" were triumphant returns to form - even if they appealed more to fans who now appreciated his remarkable musicianship rather than a wider pop audience. That said, the latter's "Black Sweat" was kind-of a hit. What happened next was odder than the internet only instrumental albums or the boxset of bootlegs. Prince released "Planet Earth" his most straightforward album for years through British newspaper the Mail On Sunday. With most of his sales from tickets for his popular live shows, this seemed a way of getting a new album into as many hands as possible without a hit single or radio play. The covermount was repeated for his next UK album "20Ten" - experiments in distribution we can line up with Radiohead's "pay what you want" model for "In Rainbows." In between these records, the latter of which was bizarrely not released in the US, a US-only (and then mail order) triple album LotusFlow3R/MPLSound came out with a 3rd disc from new soul prodigy Bria Valente. A harder edged more "classic" Prince sound, its a better record than the covermounts that preceded and followed it - yet has never had a retail release in the UK. To me, the run of albums from "Musicology" to "20Ten" show a revitalised Prince, enjoying his music, and happy to dip into his vast back catalogue of tropes. None are essential, but none are negligible.

7 3rdEyeGirl and the future

And why am I even writing an article on Prince in 2014? It turns out that Prince is back and this time he's got a band in tow, the all female 3rdEyeGirl. After a love-hate relationship with the internet, last year 3rdEyeGirl started posting on Twitter, and a number of singles appeared to download including "Rock and Roll Affair" a Purple-Rain-era style pop rock record. Then in January Prince started doing unannounced pop up gigs with his new band in the UK - first London - and rumour has it in small venues in Manchester this week. This is the artist who last time he played extensively in the UK sold out 21 nights in a row at our biggest indoor arena, the 02. In usual Prince style there have been no interviews, no explanation... but as we ponder whether he'll ever release deluxe editions of his back catalogue, or bootlegs or live albums (the rumour is that he's waiting till all his "rights" revert back to him) we've got the excitement of the man himself...playing and making new music. In a moribund musical landscape, once again the purple one is front page news.

He begins, like so many others, a 70s soul and funk artist, and his self-performed/produced debut was standard fare for the times. It was false start, only the lewd "Soft and Wet" hinting at what was to come, as he seemed to make clear on the sophomore collection by calling that one "Prince." Here he is half naked, staring at the camera, a skinny guy with long hair. The record includes his first hit, "I Wanna Be Your Lover," a brilliant piece of new wave dance pop; "I Feel for You", a later number for Chaka Khan, "Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad?" and other deep cuts that are well worth replaying.

What came next was a sidestep but an important one. "Dirty Mind" is one of the great funk records of the era, and his "blackest" record outside of the disputable "Black Album." "When U Were Mine" is the pop hit, but its the sleazy title track and the raw minimalistic "Head" that gave this album its rep. Not such a big record at the time - and virtually invisible in the UK at that time - its the album that really showed that he wasn't keen on just being the "next" Rick James or similar. 1981's "Conspiracy" continues in the same vein, but on the cover he's a suave southern gentleman, edging towards his purple period.

2. Global Superstar

Prince's 5th album "1999" was a crossover record. A mostly successful double album (he still plays deep cuts like "Something in the Water" and "Let's Pretend We're Married" in his live set) its nonetheless not any kind of prog rock statement but a series of killer dance grooves. The epoch defining "1999" and rock crossover "Little Red Corvette" amongst its massive hits. He was toe to toe with Michael Jackson at this point, "Little Red Corvette" his "Beat it", before "Thriller" hit the stratosphere. You wait twenty years for a black superstar and then two come along at once.... the control freakery had been lessened somewhat as "1999" features a named band, The Revolution. "1999" - the single - made him visible in the UK, but there was still a sense that he was a niche artist, R&B, dance floor music. The next record saw an end to that. "Purple Rain" might be the most achieved statement in rock history since "Sgt. Pepper." A mega selling record, that was actually a soundtrack to a low budget but elegantly classic film of the same name. Prince, the recluse, plays "the kid" in this "A Star is Born" style movie. But the songs in the film are perfectly placed telling the story; and even better, are utter classics. "When Doves Cry" came as the preview track, and what a preview it was - terse, minimalistic tale of domestic violence - eschewing a bass line for a staccato beat - it was a massive hit. "Lets Go Crazy" was a successful retread of "1999" whilst the epic "Purple Rain" was a guitar anthem to match Guns N' Roses or Lynyrd Skynrd. With this record and movie Prince had turned into a megastar.

3. The Imperial Phase

Six records in, Prince had made it in every way. His songs were being covered by other artists - he was acting as a mentor to chart acts as diverse at the Bangles and Sheena Easton, as well as fuelling spin off acts like the Family, Madhouse, The Time, Sheila E and others. A "Purple Rain Pt. 2" would have been expected but instead he used this platform to go left field. "Around the World in a Day" was a surprisingly tentative record. Its first single "Paisley Park" more notable for naming his new studio; whilst "Raspberry Beret" was a Beatlesque piece of power pop. Long tracks like "The Ladder" and "Condition of the heart" spoke of a more ambitious musical canvas. Yet it was a sidestep from "Purple Rain" and sold much, much less. There was no film this time - though the crassly psychedelic cover hinted at the film in the listeners head. Tellingly it wasn't really a soul album at all. Having moved our expectations, the next record "Parade" was remarkable. A film soundtrack to the black and white "Under the Cherry Moon" this fantastic record is an art pop masterpiece yet includes bonafide number one hits (in the US at least) in "Girls and Boys" and the skeletal "Kiss." Where did this come from? There are jazz interludes, and the beautiful Joni Mitchell-esque "Sometimes it Snows in April." A near perfect record that most artists would never have been able to top - the news that his next record was a double (like "1999") got us excited, but not as excited as the first single. Prince "first singles" had become a tradition - sparse, maverick and ahead of the game, "Sign O the Times" was a beautiful bleak song about crack addiction. The double album was mostly without the Revolution. Prince in his studio churning out hardly finished demos. Not since "Revolver" had a major record been so scrappily produced. Yet he knew what he was doing. In the over produced eighties, simple sounding tracks like "Hot Thing" sounded underproduced but have remained fresh years on. Its a treasure trove. The frankly amazing "If I was Your Girlfriend" (Prince as lesbian), the rock pop "U Got the Look" (Prince as Roxette), the new wave "I could never take the place of your man" (Prince as the Cars), the beautiful ballad "Adore"(Prince as Smokey) and the live funk jam "Its Going to be a Beautiful Night" (The Revolution as Parliament) among its treasures. Despite an opening salvo in "Alphabet Street" as good as any of his other first singles, the next album "Lovesexy" was transitional. It ran as a single sequence - its intricately produced, a studio record first and foremost. It feels like his first record made specifically for CD. It came out after rumours of a dark funk record "The Black Album" leaked - and only one track from the latter made the cut here.

4. Prolific Pop Prince

Prince fans were the luckiest fans in the late 80s. Whereas Michael Jackson took years between records Prince was ridiculously prolific, and each of his last four or five records had been an advance, musically, if not in sales, on the former. It couldn't go on. Not that the albums after "Lovesexy" were bad, but they no longer had the shock of the new. Sometimes there was a sense that he was spreading himself too thin - e.g. on the soundtrack to "Batman", very little of which made the actual film, or on the sprawling "Graffitti Bridge" where acts on his record label such as Mavis Staples made guest appearances. The new wave and sinewy Revolution had been replaced with a new band, the more funky, live-focussed New Power Generation. If "Batman" was a soundtrack that wasn't heard in the film, "Graffitti Bridge" was a soundtrack to a film (his third) that nobody really watched. The songs are occasionally filler though "Thieves in the Temple" was a big hit. Perhaps realising he was losing his audience a bit, his next album, "Diamonds and Pearls" was his biggest pop record since "Purple Rain" and songs like the title track, "Get Offf" and "Cream" were bonafide classics to add to the collection, the latter another to his collection of U.S. number ones. Next time we saw Prince he was in dispute with his record label, the word "slave" on his face, and a new "symbol" replacing his own name. Ridiculously perhaps, he became known as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince as he extricated himself from his Warner Bros. contract. The "symbol" album was hardly affected - it included the self mythologising rap "My Name is Prince" and unplayable on the radio "Sexy MF" - his most jazz influenced song since "Controversy." With 3 double albums in a row, and rumours of much unreleased material, the next record, the underwhelming funk album "Come" was perhaps a letdown. Yet these years though hardly imperial still saw Prince in the 90s as a major star, with many pop hits. The albums that followed would be enough for most artists' career - the poppy "The Gold Experience", the finally released "The Black Album", and the somewhat scrappy "Chaos and Disorder" were topped with a triple CD, "Emancipation". All contain gems. During his dispute with Warners, a self released single "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" became his only UK number one (though he has written number ones for Sinead O'Connor and Chaka Khan.)

5. Emancipated Prince

Part of the Warners dispute had been Prince wanting to release what music he wanted when he wanted rather than following some kind of career path. Yet we'd seen how prolific his discography was. Emancipated Prince would release and market his own music. The long rumoured quadruple album "Crystal Ball" came out on his own label, and was an archive trawling exercise, matched by Warners on the forgetable "The Vault". Prince albums for the next few years would be far from being "events" slipping out unnoticed, marketed directly to fans or by mail order (or in the early 2000s as internet downloads). "Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic" was licensed to a new label, but sold poorly. Prince continued to play live - but often his sets had nothing in common with his latest record, and versions of old songs were stretched out, funkified, changed beyond recognition.

6. Back in the Game

The diminishing returns of this fan-club only Prince were suddenly reversed in 2004 with a reinvigorated Prince putting "Musicology" out through a major label. This and the following "3121" were triumphant returns to form - even if they appealed more to fans who now appreciated his remarkable musicianship rather than a wider pop audience. That said, the latter's "Black Sweat" was kind-of a hit. What happened next was odder than the internet only instrumental albums or the boxset of bootlegs. Prince released "Planet Earth" his most straightforward album for years through British newspaper the Mail On Sunday. With most of his sales from tickets for his popular live shows, this seemed a way of getting a new album into as many hands as possible without a hit single or radio play. The covermount was repeated for his next UK album "20Ten" - experiments in distribution we can line up with Radiohead's "pay what you want" model for "In Rainbows." In between these records, the latter of which was bizarrely not released in the US, a US-only (and then mail order) triple album LotusFlow3R/MPLSound came out with a 3rd disc from new soul prodigy Bria Valente. A harder edged more "classic" Prince sound, its a better record than the covermounts that preceded and followed it - yet has never had a retail release in the UK. To me, the run of albums from "Musicology" to "20Ten" show a revitalised Prince, enjoying his music, and happy to dip into his vast back catalogue of tropes. None are essential, but none are negligible.

7 3rdEyeGirl and the future

And why am I even writing an article on Prince in 2014? It turns out that Prince is back and this time he's got a band in tow, the all female 3rdEyeGirl. After a love-hate relationship with the internet, last year 3rdEyeGirl started posting on Twitter, and a number of singles appeared to download including "Rock and Roll Affair" a Purple-Rain-era style pop rock record. Then in January Prince started doing unannounced pop up gigs with his new band in the UK - first London - and rumour has it in small venues in Manchester this week. This is the artist who last time he played extensively in the UK sold out 21 nights in a row at our biggest indoor arena, the 02. In usual Prince style there have been no interviews, no explanation... but as we ponder whether he'll ever release deluxe editions of his back catalogue, or bootlegs or live albums (the rumour is that he's waiting till all his "rights" revert back to him) we've got the excitement of the man himself...playing and making new music. In a moribund musical landscape, once again the purple one is front page news.

Monday, February 10, 2014

Harvest by Jim Crace

I have always rated Jim Crace, though looking back I realise this is only the third or fourth of his books I've read - funny how you sometimes neglect even the writers who impress you. I was surprised when I heard that "Harvest" was likely to be his last book - I hadn't quite realised he was the generation of Barnes and Amis.

Like so many of his novels "Harvest" takes place in a confined ecosystem. Crace's stock-in-trade is the circusmscribed world that though familiar is also, in his always elegant prose, somehow cut-off. Therefore "Continent" was an unnamed land; his masterpiece "Arcadia" was a generic city; and his Jesus novel "Quarantine" saw him spend forty days in the wilderness. In "Harvest" the "action" takes place in an unnamed hamlet in a past England, waiting for enclosure. There's little clue as to when or where it takes place - and I'd hazard a guess at the 12th century, in the old Wessex - but it could equally be pre-Norman, or even much later (when the Enclosures acts finally cut off the remaining common land.) I say 12th century Wessex as it was only in Wessex and Mercia where the pre-feudal commons systems survives the Norman invasion. The enclosure of the land is not so much a "modernisation" as the usurpation of English land rights - "the commons" - by others. (If its as late as the "enclosures" then it feels somehow anachronistic - as there's not even a church here; surely not possible much after the 12th century?)

The novel is the first person story as told by Walter Thirsk. He's an incomer into the unnamed Hamlet, and arrived with the incumbent master, who was the most benign of fiefs, until his own wife's death - heirless - meant that the land's title reverted elsewhere. Thirsk has had a similar bereavement. He came to the settlement, married, and then worked the land - yet he is still an incomer - and worse, as a widower who has not then taken another wife (though he has a woman whose bed he shares), is viewed with some suspicion. Yet that suspicion is based as much on family ties - or lack of - as anything real. For the Hamlet is home to several families whose blood ties are clannish. Yet despite this they rub along together, for the feudal system sees them working together on the common land for the common good, farming their own strips, but working together to bring in the harvest. It was a way of life that in this aspect remained unchanged even as recently as the 1970s when my grandparents brought in the hay, with the help of the other locals.

Yet things are about to change in the unchanging landscape in which Walter lives his melancholy widowhood. First there are newcomers, who, by common practice, have a right to be there, through their setting up of a dwelling and lighting of a fire. These newcomers: an older man, a younger man, and a mysteriously alluring slight young woman, have chosen a bad time to arrive. Just as the harvest has been brought in - if they become part of the settlement will they want part of the bounty that they did nothing to collect? Yet such questions go unanswered. Some of the master's birds have been taken, and it is the newcomers who are blamed. The two men are taken and put in the stocks for a week, a punishment less than would be warranted for such theft, but more than is required, given that in all probability they are innocent. This year's harvest celebration is haunted by this unspoken guilt. The woman, unnamed, transfixes the men of the settlement - and perhaps the women also.

But it is not these interlopers who are the biggest difficulty. A man, nicknamed "Quill" (in this book everyone has a common name, before their real one), is taking stock of the land. At first we think he's a Domesday assessor but he seems to be working on another errand. The master's rights on the land are limited - there is a new lord, who arrives later in the week, his plans are to replace the open crop lands with enclosed pastures for sheep whose wool can be sold at market. What we are seeing here is the change in English life from a subsistence economy to a rentier one. Instead of a small plot of land, governed by historic right, and kept alive by the mutual agreement of the master and his "tenants", these rights are to be overtaken by the land rights of distant capital owners. Coming out as it has in the midst of this coalition government, one can't help but see "Harvest" as an allegory, of what happens when men are stripped of the right to work for their own well-being, in the name of a rapacious capitalism. For these farmers, think zero hour contracts.

In Crace's enclosed society, the changes that happen this week are as fast as the events that overtake the community in "Straw Dogs", where a newcomer tips the balance. This is in someways a more benign world - it has survived without expectation from the outside world, but when the villagers rise up in anger at the way they are being treated, they know as well that they have no "rights" on their side - that the absent law will come at them in full force.

The first half of the novel has its faults. Not least that the events that happen seem forced in some way. Thirsk is part of the problem. He is a romantic narrator, but not necessarily an accurate one. Yet he's also distant - a Jamesian hero in a Meville-ish world. When the newcomers arrive he hears only of the woman second hand. He's absent from most of the actions in the novel, piecing them together through hearsay. Although this serves a purpose it also creates a certain lifelessness - after all this small hamlet is hardly large enough to sustain secrets, never mind indifference. In the second half of the book, as events unfold as small cataclysms that one by one change everything, you begin to understand why he's got this role. He has to be outside in order not to be caught up in it all. He can be friend to the master, concerned for the women, in love with the mysterious outsider, considerate to her pilloried husband... all seeing, but also strangely distanced from them all. In a different space and time, his knowledge could have been used to mitigate disaster - yet he's powerless to do so; seeing one thing lead to an inevitable other.

At the end he's a last remainder of what has happened: the only witness. Yet, this too has its faults. For we are none the wiser about what really has gone on. His inferences are suspect; his confidantes fled. The allegory has taken over in some ways - and the "real" people of the Hamlet dissipated to the winds. How can it have happened so quickly? It almost feels like the witchcraft that is hinted at. Here, Crace's tendency to set his books in an unspecific place comes undone a little. There are two many unanswered questions. How come this Hamlet never quite gets a church? Where are the passing tinkers and showmen that country folk are used to entertaining as they pass by? How come the village's history can be undone so quickly, so carelessly? It is an allegorical transformation and as such works up to a point. Crace's lyricism is careful but admirable. Yet it takes the action of the novel's second half to really take off. At first we are annoyed by the stubborness of the picture not to come into focus. Our unreliable narrator fails to see his world clearly enough; too much is inference or conjecture.

Worst of all, and the thing that stops the novel from succeeding fully, even on its own terms, is the figure of the unknown woman. Not once in the book does the narrator have a genuine moment with her. She is from afar, referred to as tiny, young, witchlike, yet impossible to know, given that the one time the village meets her - he is not there. He therefore conjectures what she is like; imagines that she has been discovered and bedded by any one of the village's men or the ominously strange "Quill." It is this lack of a genuine encounter which stops the novel from coming alive. How can we care about characters that are invisible? Its as if the woman and her family are merely a plot point that, though central to the telling, are actually not that important - as outsiders to the village, they are the spark, not the fire.

Like Barnes in "Sense of an Ending" or Ishiguro in "Never Let Me Go", Crace' skills as a novelist ensure that we are kept waiting on the denouement, yet like those books, the characterisation and the back story seem more suited to a long story than a novel. In a fable, its not necessary to know who, where and when these people are, in a novel, I think it is. At times "Harvest" has a quiet power, and its beyond eloquent in its central concern - this destruction of a way of life - but I'm not sure it manages entirely to ensnare the reader. We are left, like Walter Thirsk, an outsider, and our time spent here has left us with little more than when we arrived.

Like so many of his novels "Harvest" takes place in a confined ecosystem. Crace's stock-in-trade is the circusmscribed world that though familiar is also, in his always elegant prose, somehow cut-off. Therefore "Continent" was an unnamed land; his masterpiece "Arcadia" was a generic city; and his Jesus novel "Quarantine" saw him spend forty days in the wilderness. In "Harvest" the "action" takes place in an unnamed hamlet in a past England, waiting for enclosure. There's little clue as to when or where it takes place - and I'd hazard a guess at the 12th century, in the old Wessex - but it could equally be pre-Norman, or even much later (when the Enclosures acts finally cut off the remaining common land.) I say 12th century Wessex as it was only in Wessex and Mercia where the pre-feudal commons systems survives the Norman invasion. The enclosure of the land is not so much a "modernisation" as the usurpation of English land rights - "the commons" - by others. (If its as late as the "enclosures" then it feels somehow anachronistic - as there's not even a church here; surely not possible much after the 12th century?)

The novel is the first person story as told by Walter Thirsk. He's an incomer into the unnamed Hamlet, and arrived with the incumbent master, who was the most benign of fiefs, until his own wife's death - heirless - meant that the land's title reverted elsewhere. Thirsk has had a similar bereavement. He came to the settlement, married, and then worked the land - yet he is still an incomer - and worse, as a widower who has not then taken another wife (though he has a woman whose bed he shares), is viewed with some suspicion. Yet that suspicion is based as much on family ties - or lack of - as anything real. For the Hamlet is home to several families whose blood ties are clannish. Yet despite this they rub along together, for the feudal system sees them working together on the common land for the common good, farming their own strips, but working together to bring in the harvest. It was a way of life that in this aspect remained unchanged even as recently as the 1970s when my grandparents brought in the hay, with the help of the other locals.

Yet things are about to change in the unchanging landscape in which Walter lives his melancholy widowhood. First there are newcomers, who, by common practice, have a right to be there, through their setting up of a dwelling and lighting of a fire. These newcomers: an older man, a younger man, and a mysteriously alluring slight young woman, have chosen a bad time to arrive. Just as the harvest has been brought in - if they become part of the settlement will they want part of the bounty that they did nothing to collect? Yet such questions go unanswered. Some of the master's birds have been taken, and it is the newcomers who are blamed. The two men are taken and put in the stocks for a week, a punishment less than would be warranted for such theft, but more than is required, given that in all probability they are innocent. This year's harvest celebration is haunted by this unspoken guilt. The woman, unnamed, transfixes the men of the settlement - and perhaps the women also.

But it is not these interlopers who are the biggest difficulty. A man, nicknamed "Quill" (in this book everyone has a common name, before their real one), is taking stock of the land. At first we think he's a Domesday assessor but he seems to be working on another errand. The master's rights on the land are limited - there is a new lord, who arrives later in the week, his plans are to replace the open crop lands with enclosed pastures for sheep whose wool can be sold at market. What we are seeing here is the change in English life from a subsistence economy to a rentier one. Instead of a small plot of land, governed by historic right, and kept alive by the mutual agreement of the master and his "tenants", these rights are to be overtaken by the land rights of distant capital owners. Coming out as it has in the midst of this coalition government, one can't help but see "Harvest" as an allegory, of what happens when men are stripped of the right to work for their own well-being, in the name of a rapacious capitalism. For these farmers, think zero hour contracts.

In Crace's enclosed society, the changes that happen this week are as fast as the events that overtake the community in "Straw Dogs", where a newcomer tips the balance. This is in someways a more benign world - it has survived without expectation from the outside world, but when the villagers rise up in anger at the way they are being treated, they know as well that they have no "rights" on their side - that the absent law will come at them in full force.

The first half of the novel has its faults. Not least that the events that happen seem forced in some way. Thirsk is part of the problem. He is a romantic narrator, but not necessarily an accurate one. Yet he's also distant - a Jamesian hero in a Meville-ish world. When the newcomers arrive he hears only of the woman second hand. He's absent from most of the actions in the novel, piecing them together through hearsay. Although this serves a purpose it also creates a certain lifelessness - after all this small hamlet is hardly large enough to sustain secrets, never mind indifference. In the second half of the book, as events unfold as small cataclysms that one by one change everything, you begin to understand why he's got this role. He has to be outside in order not to be caught up in it all. He can be friend to the master, concerned for the women, in love with the mysterious outsider, considerate to her pilloried husband... all seeing, but also strangely distanced from them all. In a different space and time, his knowledge could have been used to mitigate disaster - yet he's powerless to do so; seeing one thing lead to an inevitable other.

At the end he's a last remainder of what has happened: the only witness. Yet, this too has its faults. For we are none the wiser about what really has gone on. His inferences are suspect; his confidantes fled. The allegory has taken over in some ways - and the "real" people of the Hamlet dissipated to the winds. How can it have happened so quickly? It almost feels like the witchcraft that is hinted at. Here, Crace's tendency to set his books in an unspecific place comes undone a little. There are two many unanswered questions. How come this Hamlet never quite gets a church? Where are the passing tinkers and showmen that country folk are used to entertaining as they pass by? How come the village's history can be undone so quickly, so carelessly? It is an allegorical transformation and as such works up to a point. Crace's lyricism is careful but admirable. Yet it takes the action of the novel's second half to really take off. At first we are annoyed by the stubborness of the picture not to come into focus. Our unreliable narrator fails to see his world clearly enough; too much is inference or conjecture.

Worst of all, and the thing that stops the novel from succeeding fully, even on its own terms, is the figure of the unknown woman. Not once in the book does the narrator have a genuine moment with her. She is from afar, referred to as tiny, young, witchlike, yet impossible to know, given that the one time the village meets her - he is not there. He therefore conjectures what she is like; imagines that she has been discovered and bedded by any one of the village's men or the ominously strange "Quill." It is this lack of a genuine encounter which stops the novel from coming alive. How can we care about characters that are invisible? Its as if the woman and her family are merely a plot point that, though central to the telling, are actually not that important - as outsiders to the village, they are the spark, not the fire.

Like Barnes in "Sense of an Ending" or Ishiguro in "Never Let Me Go", Crace' skills as a novelist ensure that we are kept waiting on the denouement, yet like those books, the characterisation and the back story seem more suited to a long story than a novel. In a fable, its not necessary to know who, where and when these people are, in a novel, I think it is. At times "Harvest" has a quiet power, and its beyond eloquent in its central concern - this destruction of a way of life - but I'm not sure it manages entirely to ensnare the reader. We are left, like Walter Thirsk, an outsider, and our time spent here has left us with little more than when we arrived.

Sunday, February 09, 2014

What's a Story?

We grow up with stories. Aesop's fables, Bible stories, Famous Five and Secret Seven, Dennis the Menace and the Avengers, SF or school stories....

Yet when we say "short story" I think we're talking of something different - a genre of (mostly) 20th century literary fiction.

Whereas there are poets who only read poetry, it would seem to me a little odd to just read short stories, even if you like them - surely the short story is a subset of prose fiction? Yet that stories are different than novels, is also generally true. But then you read something like Zadie Smith's recent stand-alone story "The Embassy of Cambodia" and it has the same heft and scope - and open-endedness - as her novels, yet at the same time is tighter, more focussed, more self-contained.

What have we got then between the open-ended and the self-contained... there hovers the story.

Some of the most famous stories we have are from writers me more often associate with the novel - such as E.M.. Forster's "The Machine Stops" or Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily". Then there are the specialists in the form - Chekhov, Mansfield, Munro. Modernism took to the short story: James Joyce's "The Dubliners", Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc. but maybe this was a feature of the market - of little magazines and high paying mass market publications?

Writers have always written them, but not all writers. There are quite a few novelists who prefer the bigger canvas; such as Anthony Burgess whose vast writings gives us just one later book of short stories. And because a short story can actually be quite long - (that Forster is 12,000 words, David Foster Wallace's shorts often ran to many, many pages) - its hard to generalise.

But generalise we do. We're living in an age of the short story it seems - with new prizes for the genre from the Sunday Times and the BBC (though both seem to prefer established novelists given the choice), a couple of well regarded "best collection" prizes, panels on the short story at most literary festivals. It should be an easy read in busy times - though the evidence is that we don't read a short on the bus, preferring a few pages of the big novel, and that good short stories require a level of attention that we don't always have to give.

With a proliferation of creative writing courses you can see the appeal of the short - it can be read in a sitting. There is somewhere probably it can get published, whilst an unpublished novel languishes unforgiven for years in the bottom drawer. The story has an after life as an idea for a poem-film or a short play. It exists, oddly enough, in that strange cottage industry world familiar to contemporary poetry - of little magazines and live readings. Often poets (who sometimes don't read novels) write them.

The only thing that made me think I could write a novel was that I had written a few stories. I knew I could knock together 5,000 words or so, with a denouement of sorts. What was a novel other than a dozen or so of those of these denouements, connected together into a rough plot? (The younger me was remarkably naive, or deliberately self-deceiving.) Yet I remember - at a very early stage - perhaps when I was in my first or second year at university (reading - revelation that it was - Sherwood Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio" or Fitzgerald's stories, or "Men Without Women") despairing a little that outside of Science Fiction (a disregarded genre even more then than now) I couldn't really write a story. My SF was somewhat of the William Gibson kind, even - I think - before I'd read Gibson. (I'd been reading Blish, William Burroughs and comic books, as well as watching "Blade Runner" and "2001" before I'd even heard of "Neuromancer"). Actually my true SF hero was a true genius of both that genre and the short story itself, Harlan Ellison's whose "Jeffty is Five" is a better story than I will ever write.

I had started writing seriously that summer of '86 - and had laboriously typed up and stapled a number of articles, poems, two or three SF stories, and an ongoing serial into a vague fanzine. A short story could be about anything, I reckoned, it was just writing after all...

...I was asked a few years ago when I first took my writing seriously. Part of me wanted to say "always" but I know exactly when it was. In my 3rd year at university I wrote a long short story about a girl with learning difficulties called "Elly Condor." I can't quite remember the story itself - though it exists somewhere - but I rewrote it several times before writing up a fair copy which I was so pleased with I remember giving to a friend to read. She was very complimentary. The story was perhaps the first non-SF one that was entirely out of my imagination (though I think choosing an inarticulate narrator came from reading "The Sound and the Fury.")

After university it was novels that took up my time.... yet a novel was a hard sell even back then - and took forever. Wanting to share my writing with a penfriend (who years later would turn out to be internationally acclaimed for her short stories) I'd written a story as an "application" to the M.A. in creative writing at UEA. Rather than just send the typescript I again went dozen the fanzine route - and realised I'd need to write some more to make it into a proper magazine. Over the next few years this "fanzine" taught me how to write short stories - every couple of months I had another 20 or so pages to fill. By the time I got to do my MA in novel writing at Manchester, I'd quite a few short stories that I was proud of.

I mentioned SF as a formative influence - and much of my writing remained somewhat "slipstream" - if not exactly futuristic - but I was also massively influenced by American writing and it was a trip to the US in 1995 which really informed my writing - and the story that I sent to UEA was one of those "American Stories". Again, writing outside of myself gave me a confidence in short story writing that I never quite managed in a novel: the long length tended to gobble me up and throw me out the other side. It needed everything of me; whilst a short story could have an idea.

So since 1996 I've written short stories regularly. A few of these got published in small magazines. I don't even think this was my aim. I certainly didn't always spend enough time on the 2nd/3rd drafts - but what I lost in haste, I gained in bravery. If a story didn't turn out that great, I put it down as an experiment. Some of these became key stories.

Over the last decade my fiction sometimes feels like its dwindled to a trickle - a couple of finished stories a year maybe. One thing is that I've written so many. Maybe I've written enough? I've not a "public" for them after all. Nowadays I tend to come up with an idea and then try and find the form to make it work. Sometimes this is traditionally linear, other times wilfully experimental. I do rewrite now - but realise I can sometimes write the life out a story.

I sometimes read short story collections and marvel at a writer who attacks the same subject from different angles, or is exploring a single imaginative universe or character group, or style. My debut short story collection should be called "a compendium", its that diverse. I wish the empty page wasn't always so daunting. I wish there was finished story to complete the title I began in 1999 "Nathan Adores a Vacuum" or that I'd found a way to write the World War II referencing story "the Dugway Proving Grounds" that I began nearly a decade ago. I also wish the story I wrote last week wasn't quite so wilful.

In other words, when I read about the renaissance of the short story I do wonder what we mean. For me, its a key element of prose fiction - it can sometimes be part of a novel, or a number of stories can be the equivalent of a novel; other times the best short stories seem to be perfect one-offs, literary equivalents of Martha and the Muffins' "Echo Beach" (and I had a period of using song prompts to help me write stories, so have a story with that title as well!)

For me, I think the short story as we seem to see it in its "renaissance" is not actually the short story as I see it or even as I write it. This seems a genre of the "proper short story" perhaps subtitled "the Hemingway story" or "the Chekhov story" or "the Cheever story" or "the Munro story." Its not to knock those - but you know the type; a disembodied scene with characters that you wonder if they could ever possibly exist outside of fiction, meeting for something meaningful, and something is left unsaid. These things deservedly win prizes but they seem to belong to some kind of literary nostalgia circuit - for if the short story is really having a renaissance it has to be as some kind of experimental testing ground for new ideas. Outside of the increasingly crowded flash fiction world, I'm not sure I see that much of it - but please, point me in the right direction....

...is there or has there been a British collection that is as wayward as George Saunders book, or as wilfully strange as a David Foster Wallace one; or as keen to poke fun at the genre itself as Jennifer Egan's "Black Box?"

So, rant over, I don't really know if I love, like, or am indifferent to the short story - I think, like everything, give me "Jeffty is Five", "Career Move", "A Rose for Emily", "Hills Like White Elephants", "A Sad Day for Bananafish", lots of Helen Simpson, Andre Dubus and Lorrie Moore, and I'm a happy man. I like individual stories by a wide range of contemporary writers, some my friends (real world and Facebook), and on the odd occasion that my own get in amongst them, I'm pleased as punch -

- but I write them because I still don't know the answer to that provocation at the top of this blog post. I don't know. I don't know. And then, occasionally, just occasionally, I write one or read one, and go... "oh, that's it."

Yet when we say "short story" I think we're talking of something different - a genre of (mostly) 20th century literary fiction.

Whereas there are poets who only read poetry, it would seem to me a little odd to just read short stories, even if you like them - surely the short story is a subset of prose fiction? Yet that stories are different than novels, is also generally true. But then you read something like Zadie Smith's recent stand-alone story "The Embassy of Cambodia" and it has the same heft and scope - and open-endedness - as her novels, yet at the same time is tighter, more focussed, more self-contained.

What have we got then between the open-ended and the self-contained... there hovers the story.

Some of the most famous stories we have are from writers me more often associate with the novel - such as E.M.. Forster's "The Machine Stops" or Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily". Then there are the specialists in the form - Chekhov, Mansfield, Munro. Modernism took to the short story: James Joyce's "The Dubliners", Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc. but maybe this was a feature of the market - of little magazines and high paying mass market publications?

Writers have always written them, but not all writers. There are quite a few novelists who prefer the bigger canvas; such as Anthony Burgess whose vast writings gives us just one later book of short stories. And because a short story can actually be quite long - (that Forster is 12,000 words, David Foster Wallace's shorts often ran to many, many pages) - its hard to generalise.

But generalise we do. We're living in an age of the short story it seems - with new prizes for the genre from the Sunday Times and the BBC (though both seem to prefer established novelists given the choice), a couple of well regarded "best collection" prizes, panels on the short story at most literary festivals. It should be an easy read in busy times - though the evidence is that we don't read a short on the bus, preferring a few pages of the big novel, and that good short stories require a level of attention that we don't always have to give.

With a proliferation of creative writing courses you can see the appeal of the short - it can be read in a sitting. There is somewhere probably it can get published, whilst an unpublished novel languishes unforgiven for years in the bottom drawer. The story has an after life as an idea for a poem-film or a short play. It exists, oddly enough, in that strange cottage industry world familiar to contemporary poetry - of little magazines and live readings. Often poets (who sometimes don't read novels) write them.